We are the latter chapters of a book authored by our ancestors.

As such, the details that we’ve written find deeper meaning when we look back at what came before them. Where were our grandparents raised? What were their ambitions? Who were they and how did they define success? What if we are unwittingly living out their unfulfilled dreams? Knowing the answers to these questions might bring our image of achievement into focus.

Often, when we try to account for our own, or someone else’s ambition we will look to immediate parents for evidence. In the book, “Children of the Dream: The Psychology of Black Success” by Audrey Edwards and Dr. Craig Polite, numerous interviewees speak of their maternal or paternal influences.

Kathleen Knight, who was a Human Resources Manager at Ford Motor Company credited her parents with her success as they provided her with early opportunities to develop her talent. In particular, she noted how her mother’s wisdom, even as a elevator operator, helped Kathleen rise within the corporate world. Clarence O. Smith, one of the original founders of Essence Magazine, recounted how his father lit his business acumen by explaining the principle of risk and reward in the enterprise system. Arlene Smith, who was a service manager with a large telecommunications firm back in the nineties spoke of how her father was a role model, having shared the lessons he learned from the adversity he faced as a General Electric executive.

By contrast, “Our Kind of People” by Laurence Otis Graham, takes the long view. The book recounts his observations of who he calls, “The Black Elite”, people who have experienced success for generations, and have positioned their progeny to follow in their footsteps. As Graham goes through a litany of those he considers to be in that elite class, included were “those who could look back at two or three generations and point to relatives who owned insurance companies.”

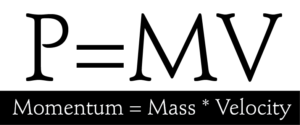

Many considered the book off-putting because of the way Graham seems to question the exclusivity of the upper class Black society he describes while yet reminding the reader that he is happy to have one foot in it. However, the stories he told about tradition, custom, and privilege caused me to think about our predecessors’ experiences as “inter-generational momentum”. While their experiences may not amount to predestination, they may influence us in ways we haven’t yet acknowledged.

The possibility for this kind of momentum is also made clear in Henry Louis Gates’ Jr.’s show, “Finding Your Roots”, on PBS. During each episode, Dr. Gates researches the personal and genealogical history of his guests. When he researched Oprah Winfrey’s past, what he found shocked her, but also gave her clarity. One of her ancestors managed to purchase property in the south during the 1800s and founded a school on it. She immediately saw the connection between her great grandfather’s ambition, and her founding of the Leadership Academy for Girls in South Africa.

This holiday season, as we reconnect with our extended families, we have the opportunity to ask the kinds of questions that reveal deeper truths. Even if we have not experienced all the success we envisioned when we were younger, ambition and progress will continue its inter-generational flow through us to our children when we share those truths with them.

Inside a briefcase that my father had been using, I found a brief essay he had written titled, “My Son”. He had just passed away, so finding it was like hearing his voice one last time. In it, he talks about what I was doing then, but the larger story is that his essay was a writing assignment. After I graduated from college, he went back to school to learn how to read and write. He was intelligent, but life circumstances removed him from school after third grade. He may not have been “their” kind of people, but he was mine—having never given up on the possibility of furthering his education. This is among the stories I will share with our sons.